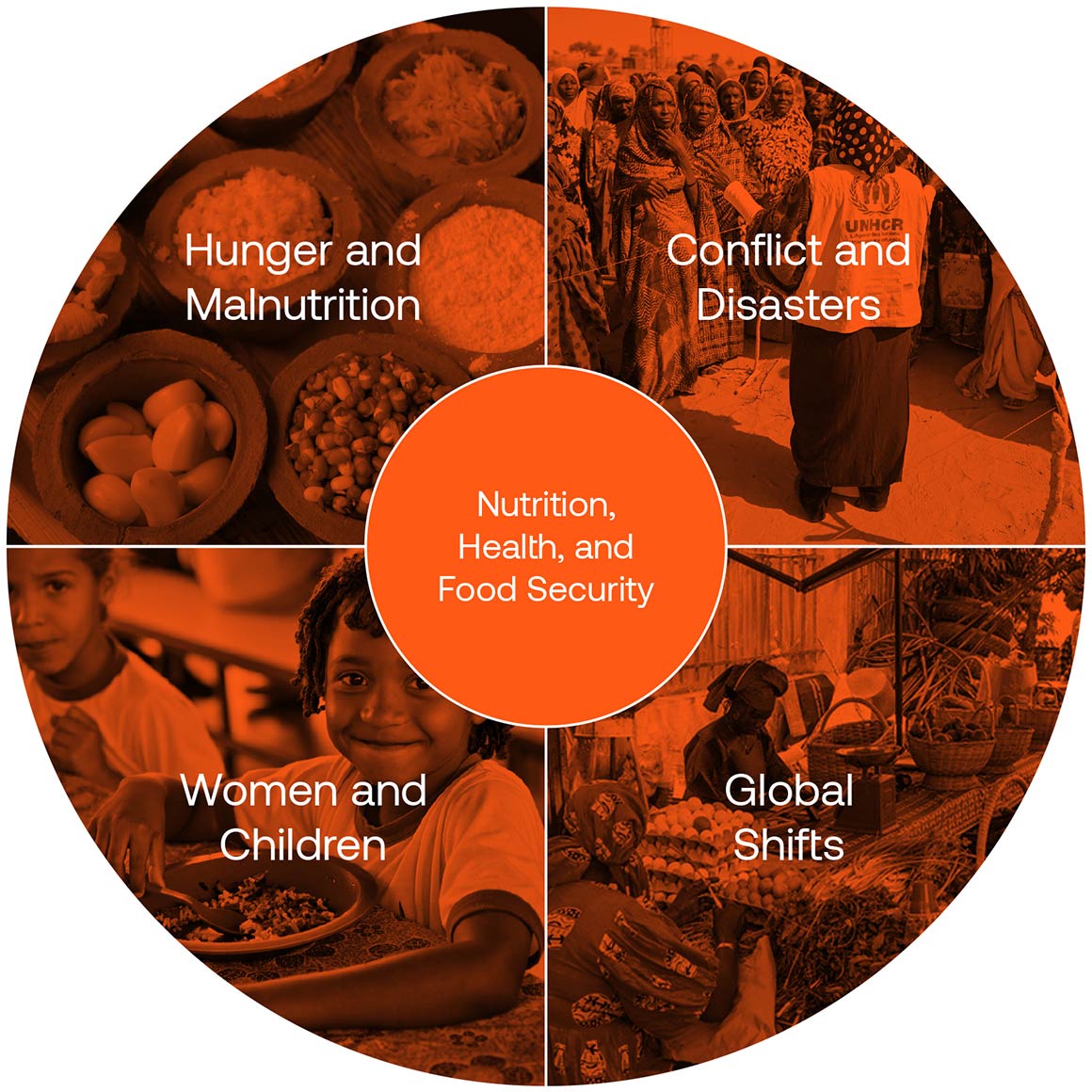

Nutrition, Health and Food Safety

Nutrition-sensitive food systems provide culturally appropriate, affordable, available, diverse, and safe diets that ensure nutrition, health, and food security.

When coupled with women’s empowerment to make informed dietary choices and nutrition-sensitive programs such as social protection to address affordability, they can strengthen family nutrition in low- and middle-income countries. National programs that incentivize sustainable nutrition-sensitive food production, distribution, and consumption across crop, livestock, aquatic food, and agroforestry systems are essential for long-term human and planetary health and, with the right policy and investment support, can also drive market demand, boost livelihoods and improve diets and nutrition.

Whatever foods we produce should be nutrient-dense, robust, culturally acceptable, and part of a healthy, safe diet.”

Recommendations

for Decision-Makers

- Consider the whole food system—farm to consumer, and links to other sectors, like education and infrastructure—when working to achieve sustainable healthy diets (accessible, affordable, safe, and equitable, while being culturally acceptable, with low environmental impact).

- Adopt an integrated mix of food-based strategies such as biofortification and increased dietary diversity to address nutrition, health, and food security. No single approach can effectively address the complex dietary needs of diverse populations and deliver whole diets that are healthy, affordable and sustainable.

- Make collaborative decisions across multiple sectors – no single actor can make the changes needed without finding synergies and identifying trade-offs, for example, between health, education, finance, social protection, and agriculture actors, and through engagement with both large and small agribusinesses.

- Take care when introducing alternative dietary options into diverse local food systems and population groups. Without considering consumer preferences, cultural acceptance, affordability, and market demand, efforts may fall short or, worse, disrupt livelihoods and food and nutrition security.

- Invest in improved aquatic foods and livestock breeds as well as local staple foods such as roots, tubers, bananas, and legumes. Along with greater access to fruits and vegetables, these staples can drive dietary, nutritional, and economic gains, especially in sub-Saharan Africa and large ocean states, where they are well-suited to a changing climate.

- Balance emergency responses to conflict and natural disasters that address acute hunger with long-term efforts to build resilient food systems that ensure nutritious, diverse, balanced, and safe diets.

Challenges

Hunger and Malnutrition

In 2023, nearly a third of the global population (2.33 billion) faced food insecurity, impacting public health and economic stability.

Malnutrition, driven by poor diets, includes people not getting enough food or the right balance of nutrients to stay healthy. This fuels diseases like diabetes and obesity, especially in Latin America, Africa, and Asia-Pacific, where rates are rising.

Conflict and Disasters

In conflict-affected and fragile regions, the situation is even more critical. In South Sudan, 43% of children are unable to access a nutritionally adequate diet, a figure that rises to 63% in Somalia and a staggering 90% in Gaza (Kadiyala, 2024).

Compounding this issue, conflict, violence, and climate-induced disasters forced 71.1 million people into displacement in 2022, disrupting food production systems and further destabilizing food security.

Women and Children

Low- and middle-income countries face GDP losses of 3–16% from malnutrition due to reduced productivity, with women and girls disproportionately impacted.

Maternal malnutrition affects both mothers and children, contributing to 45% of global child mortality and hindering development.

Over half of children under five and two-thirds of nonpregnant women of reproductive age lack essential nutrients like iron, zinc, and vitamin A or folate.

Global Shifts

Progress toward ending hunger and ensuring healthy, affordable diets is stalling due to the climate crisis, rising geopolitical tensions, population growth, poverty, rapid urbanization, and shifting consumption patterns (ISDC, 2023).

What Food Systems Science Tells Us

Scientific food-based research underscores the need to address the challenges of nutrition, human health, and food security in food systems in an integrated way to ensure that healthy diets are accessible, affordable, desirable, available, and culturally relevant. This requires innovations across production, markets, food supply chains, and consumption in urban and rural centers that consider local economic and social conditions, supported by deeper structural drivers of poor diets and malnutrition, such as poverty. This is particularly important under climate change, which drives reduced food production due to changes in rainfall and temperature.

Science tells us that an mix of food-based strategies is crucial to help tackle malnutrition (Figure 16). No single approach can effectively address the complex nutritional needs of diverse populations. Many factors drive consumption, for example desirability, affordability, accessibility and availability of foods. Success comes from collaborating across a range of public sectors like health, education, finance, and agriculture, along with engagement with the private sector, including both large and small agribusinesses and the food industry. For instance, consumer dietary choices can be driven by government-led actions on nutrition education, subsidies, pricing, food safety standards, and labelling requirements. These, in turn, drive private sector investment and innovation to meet the resulting increased market demand for healthy foods.

Dietary diversification and biofortification are two complementary strategies for improving the nutrient status of populations and raising levels of nutrition, which are examined here.

In terms of dietary diversity, over the last 50 years, global diets have become more similar. For example, humans have historically cultivated approximately 6,000 plant species for food. Today, just 200 significantly contribute to global diets, with a similar decline in livestock breeds, and fish strain diversity (FAO, 2019). Reversing this trend requires a better understanding of the nutrient content of this treasure trove of food sources to identify promising options for future research and development, understanding their accessibility, such as through community mapping of local biodiversity, and the impacts that the changing climate may have on nutritional value.

Investing in diverse crops, livestock, and aquatic foods across production systems, markets, and diets is essential for promoting dietary diversity and resilience through agrobiodiversity. This approach helps overcome barriers at different decision-making and implementation levels (Figure 17).

Agrobiodiversity defined

Agrobiodiversity (agricultural biodiversity) is a subset of biodiversity. It encompasses the variety and variability of animals, plants, and microorganisms that are necessary for sustaining key functions of the agroecosystem, including its structure and processes for, and in support of, food production and food security (FAO, 1999a). Biodiversity and ecosystems in relation to food systems are discussed in more detail in the Environmental Health and Biodiversity Section.

Biofortification of staple foods—a food eaten often and in such quantities that it constitutes a dominant portion of a standard diet—is a complementary approach to diet diversification that can also enhance health. Biofortification is not intended to increase the consumption of staples but rather to substitute some or all non-biofortified major staple foods with better and more micronutrient-rich varieties.

Through CGIAR’s national agricultural research and extension systems (NARES) partnerships, we have introduced new varieties of biofortified crops to target specific micronutrient deficiencies. Examples include vitamin A-rich orange sweetpotato and maize, zinc-fortified rice and wheat, and high-iron and zinc sorghum, and high-iron beans. See Figure 18 for some global impacts from CGIAR’s crop biofortification work.

Animals produced for food or food-related products constitute 40% of the value of global agriculture and support the income and livelihoods of one in five people, mostly in low- and middle-income countries (WOAH). Foods derived from aquatic and livestock sources are particularly beneficial for maternal and infant nutrition during the critical first 1,000 days of life. These include the inclusion of indigenous small fish into local diets to deliver health benefits to communities facing malnutrition.

Participatory breeding programs—when farmers, breeders, and other relevant stakeholders work together to develop new varieties—help ensure that the resulting innovations suit local needs and are integrated into local diets, markets, and food supply chains. Closing the gender gap in vulnerable communities is also crucial for achieving sustainable nutritional outcomes. Women play a pivotal role in household nutrition and childcare decisions; empowering them with the knowledge, resources, and market access they need to grow, purchase, and prepare healthy foods has been demonstrated to have positive effects throughout communities. Increasing women’s capacity to grow food (e.g. by strengthening home garden production), and boosting their bargaining power (e.g. through cooperatives), create a strong foundation for broader nutrition, social, and economic benefits.

As urbanization increases, it is equally important to promote nutritious food production in cities. Community-based urban farming programs can support low-income households by enabling them to grow their own food, reduce household expenses, create additional livelihoods, and help reduce food deserts. To complement this, regulatory frameworks must focus on improving food safety and quality in informal markets through better food labelling, transparency, and traceability.

Finally, policy and investment efforts can incentivize the production of nutritious food by redirecting subsidies, while disincentivizing the consumption of ultra-processed foods through tax measures and regulations. Investing in initiatives that reduce food loss and waste across supply chains, for example, improving cold chain infrastructure for transport of fresh produce and improved seed systems, is also vital to overcoming barriers faced when transforming food systems and ensuring that sustainable, healthy diets are accessible and affordable to all. Additional efforts to provide nutrition education and encourage uptake include subsidies for healthy diets, public procurement programs, school feeding initiatives, and food system improvements such as cold storage, transport infrastructure for fresh produce, and improved seed systems.

Questions and Answers:

What Do Decision-Makers Need?

During the consultation, four critical questions emerged where decision-makers felt further guidance was needed. Here, we present a menu of answers to give a flavor of some of the available options and to show how they can be adapted to diverse local, national, and regional contexts.

More options are available here.

How can scientific research guide policy and incentives to promote biodiversity in food and nutrition?

Decision-Maker Question: “How can scientific research guide policy and incentives to promote biodiversity in food and nutrition?”

One Answer: Mixing menus through policy incentives in Brazil, Kenya, Sri Lanka, and Türkiye

In 2006, the Convention on Biological Diversity launched an initiative to integrate biodiversity for food and nutrition into national food and nutrition strategies—an approach that no country had adopted at the time.

In response, Brazil, Kenya, Sri Lanka, and Türkiye led a Global Environment Facility (GEF)-funded initiative, implemented by the UN Environment Program (UNEP) and the UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), and supported by CGIAR, who oversaw its global coordination. Its success came from collaboration across sectors focused on three actions:

- Producing strong evidence

- Shaping policies and markets

- Raising public awareness.

It brought together experts, researchers, government officials, educators, farmers, chefs, and communities to recognize and promote the nutritional value of often-overlooked crops and wild plants. A major achievement was generating food composition data demonstrating the nutritional benefits of many local crops and wild species. This evidence shaped new policies, such as incorporating diverse species into school meal programs and supporting local, women-led food businesses rooted in traditional knowledge.

In Brazil, the initiative led to a groundbreaking ‘Socio-Biodiversity’ policy in 2016 (updated in 2018) that identified 101 regional species as nutritious foods eligible for government procurement. This policy supported government initiatives like the Food Acquisition Program, the Minimum Price Guarantee Policy for Biodiversity Products, and the National School Feeding Program (Figure 19). These efforts helped to improve the diets of around 40 million students who rely on school meals.

The Ministry of the Environment in Brazil emphasized the importance of innovative partnerships to connect knowledge, policy, and markets, and the need for dedicated champions with the vision and leadership to mobilize resources and stakeholders. It has also underscored Brazil’s rich agricultural biodiversity and demonstrated how government procurement schemes could incentivize sustainable production.

The Biodiversity for Food and Nutrition approach is now being piloted in Asia as part of plans to scale its impact.

Which Decision-Makers Will Find This Useful?

Those implementing National Biodiversity Strategic Action Plans (NBSAPs) as part of work to deliver on United Nations (UN) Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) goals, Ministries of Environment and Forestry, Agriculture, Health, Education, Rural Development, Social Development, Finance and Planning, non-governmental organizations (NGOs) like the Rural Outreach Programme in Kenya, The Green Movement, and the Community Development Centre in Sri Lanka, Community-based organizations (CBOs), women’s groups, youth groups, cooperatives and farmer organizations.

Resources for Decision-Makers

Free book

Diversifying Food and Diets: Using Agricultural Biodiversity to Improve Nutrition and Health

Contact

Teresa Borelli

Scientist, CGIAR – Alliance of Bioversity International and CIAT

t.borelli@cgiar.org

How can we build and implement strategies that result in better health for people, animals, and the environment?

Decision-Maker Question: “How can we build and implement strategies that result in better health for people, animals, and the environment?”

One Answer: Integrated service delivery in Ethiopia, Kenya, and Somalia

The One Health for Humans, Environment, Animals, and Livelihoods (HEAL) initiative is an example of how adopting One Health principles can support vulnerable pastoralist communities, their livestock, and the rangelands they depend on. One Health is a way of thinking that recognizes the interconnectedness of human, animal, and environmental health. It considers aspects of food systems around preventing and managing diseases that spread between animals and humans, ensuring safe food and water, and reducing the use of antibiotics in food systems to combat antimicrobial resistance (WHO, 2018).

In the Horn of Africa, pastoralists face challenges accessing quality human and animal health services. Further, the rangelands they depend on are highly degraded by over-grazing and land use changes compounded by climate change. There is also a lack of skilled personnel working to improve rangeland health. One Health Units (OHUs), a project led by VSF-Suisse and supported by the International NGO Amref Health Africa, provide much-needed services for these remote and underserved populations by addressing human, animal, and environmental health together (Figure 20).

Static OHUs are set up in community gathering locations such as water points, while mobile units travel along pastoral routes. Services include livestock and human vaccinations, health education, nutrition screening, and support to restore rangeland health. Government employees and community-based actors representing human, animal, and environmental health usually staff the OHUs, while community members provide oversight through local Multistakeholder Innovation Platforms. They do this alongside local government One Health Taskforces who provide training and supervision, and support planning and monitoring of the OHU.

Currently, the model is being implemented in pastoralist areas of Ethiopia, Kenya, and Somalia through the HEAL project, with support from international non-governmental organizations (INGOs). Its flexible design allows customization to meet local needs and makes it adaptable for other countries with remote pastoralist communities.

In the first three years of the pilot:

- 1.1+ million livestock received vaccination services, benefitting 77,600+ households.

- 33,600+ people were vaccinated, 60,000+ people received health education, 84,800+ people received curative services and 54,500+ received nutrition screening.

- 1.5+ million hectares of rangeland were under a new Rangeland Management Plan, with 48 hectares under intensive restoration.

In the next phase, the model will be evaluated for its impact on health behavior change, financial efficiency, and value for money.

Which Decision-Makers Will Find This Useful?

Stakeholders invested in improving rangelands. National and local policymakers such as those in Ministries of Finance, Planning, Health, Agriculture, and Environment. Non-governmental organizations (NGOs). Regional Health and Livestock Bureaus, as well as other entities in pursuit of progress towards the 2030 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

Resources for Decision-Makers

Case Study

Contact

Siobhan Mor

CGIAR – International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI)

s.mor@cgiar.org

How can we best target specific nutrition gaps that are affecting people in our countries?

Decision-Maker Question: “How can we best target specific nutrition gaps that are affecting people in our countries?”

One Answer: Biofortifying crops in Pakistan to tackle zinc deficiencies

In Pakistan, zinc deficiency affects more than 50 million people, nearly 25% of whom are women, and 20% are children under five. Zinc is essential for more vital functions than any other micronutrient, supporting metabolism, gene activity, hormones, and the immune system. In children, low zinc levels can slow growth, affect brain development, weaken immunity, and hinder skin and bone healing.

Biofortification— the development of varieties with enhanced concentrations of essential micronutrients—offers a promising and sustainable strategy to fill these gaps. Wheat is a dominant part (staple) of a standard diet in Pakistan, particularly for resource-poor farming communities who cannot afford or have low access to foods like fruit and meat products. It is consumed at an average of 130 kg per person annually and grows on over nine million hectares. This means that enriching wheat with zinc presents an effective pathway to address this deficiency and deliver essential nutrients to millions of people while not compromising yields.

A 20-year partnership between CGIAR and Pakistani scientists has yielded substantial advancements in biofortification. Five zinc-enriched wheat varieties have been released, including Akbar-19, the country’s most successful variety. It is appreciated for its enhanced nutritional profile, high grain yield, disease resistance, resilience against lodging—when wheat plants fall over or lean too much, usually due to strong wind, heavy rain, or weak stems—and it is excellent for chapati (flatbread) making. Almost 100 million consumers consume it annually.

CGIAR, in partnership with national agricultural research and extension systems (NARES), national research groups, and organizations like HarvestPlus and the Global Alliance for Improved Nutrition (GAIN), has supported local seed production to reach remote areas facing food shortages. By involving farmers and consumers and using quicker seed-growing methods, adoption has increased even faster.

Today, 50% of the total area planted to wheat in Pakistan is producing biofortified varieties, and studies show that consuming zinc-enriched wheat increases overall zinc intake by 21%, significantly improving population health outcomes.

Biofortified wheat’s success extends beyond Pakistan. More than two dozen high-yielding, high-zinc wheat varieties derived from CGIAR research have been released in India, Nepal, and Bangladesh. These varieties, grown on over 6 million hectares across South Asia, reach millions of farmers through public-private partnerships, contributing to regional efforts to combat malnutrition.

Which Decision-Makers Will Find This Useful?

Local and national-level policymakers including Ministries of Agriculture, Health and Finance. Non-governmental organizations (NGOs), development agencies and research institutes focused on maternal and child nutrition and delivering on food and nutrition security programs. Entities in pursuit of progress towards the 2030 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

Resources for Decision-Makers

Case for Investment

Contact

Velu Govindan

Principal Scientist | Head- Bread Wheat Breeding, CGIAR Global Wheat Program, Mexico, CGIAR – International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT)

velu@cgiar.org

Which fish are best bets for nutrition outcomes?

Decision-Maker Question: “Which fish are best bets for nutrition outcomes?”

One Answer: The global GIFT that keeps on giving

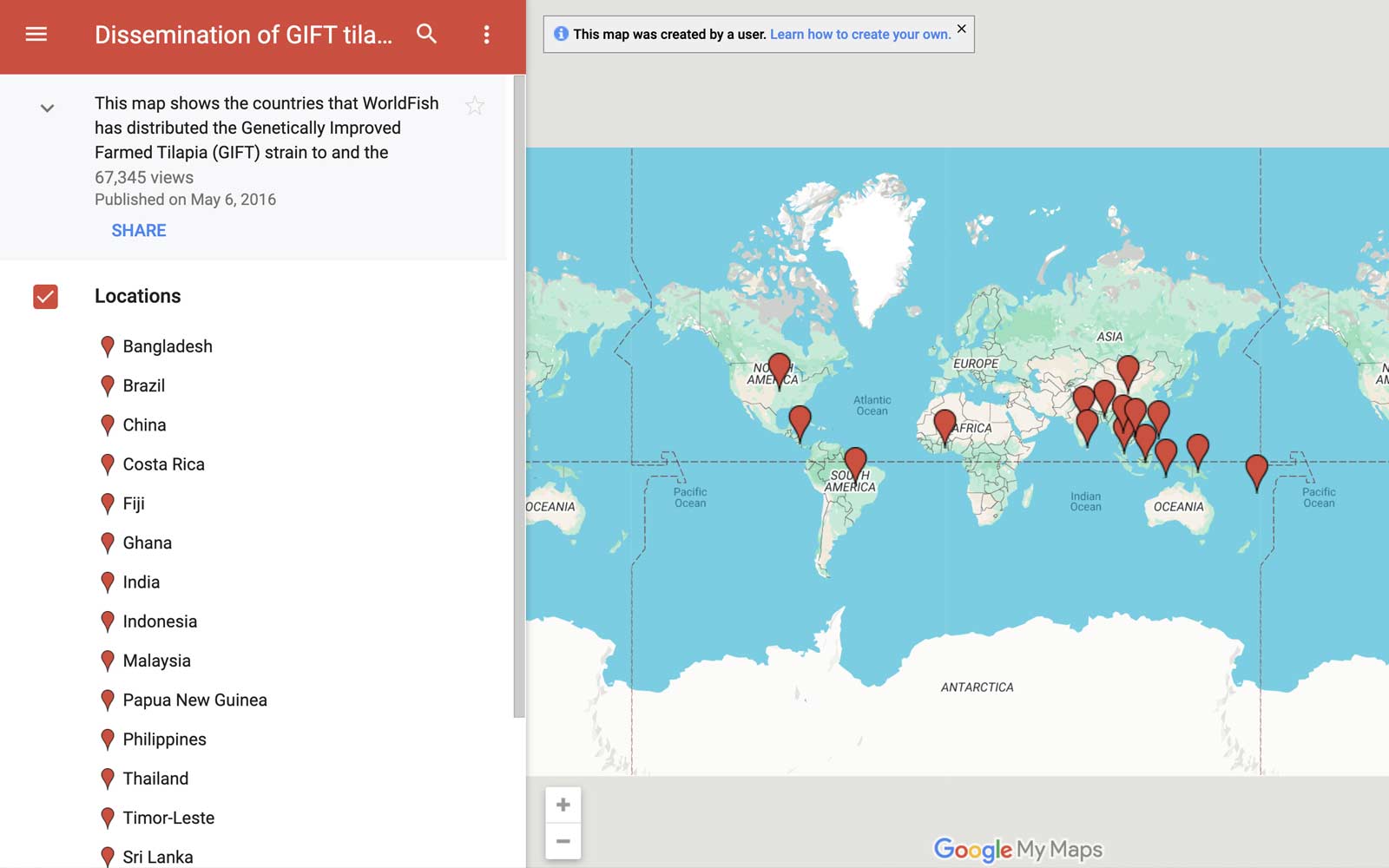

Aquaculture, or fish farming, is the world’s fastest-growing food production sector. It supplies almost half of the fish consumed globally, and by 2030, production is expected to grow by a further 40% to meet rising demand. A key factor in this increase is the use of improved fish strains.

Fish is a crucial source of nutrition, especially in the world’s poorest countries, where it provides more than half of the animal protein people consume. Tilapia is a particularly valuable species because it is affordable, rich in protein, vitamins, minerals, and essential fatty acids that are vital for good health, and easy to farm. It grows quickly and adapts to a wide range of environments.

Concerns about low productivity in tilapia farms led CGIAR to review global tilapia genetic resources—the varieties of tilapia used in fish farming—from 1980 to 1987, identifying inadequate quality seed (juvenile) supply and declining fish performance in many aquaculture systems in Asia as major issues. This resulted in CGIAR’s collaboration with partners from the Philippines and Norway to launch the Genetically Improved Farmed Tilapia (GIFT) project. This initiative developed a faster-growing strain of Nile tilapia for both small-scale farmers and commercial purposes, which grows faster and more efficiently than previous strains.

Today GIFT makes up more than half of the world’s tilapia production and is produced across five continents (Figure 21).

Some key examples include:

- Timor-Leste: GIFT supports the National Aquaculture Development Strategy (2012-2030), which aims to produce 12,000 tons of farmed fish annually. This effort is expected to increase fish consumption to 15 kg per person per year to help tackle malnutrition. Tilapia is also being served in school lunches to enhance fish consumption in rural areas.

- Nigeria: Under the government’s five-year Agricultural Technology and Innovation Policy, launched in 2022, scientists are pioneering aquaculture approaches to boost local protein supplies, reduce fish imports, enhance climate resilience, support small-scale farmers, and create 500,000 new jobs in the aquaculture sector.

- Viet Nam: Tilapia production has grown significantly making the country the seventh-largest producer in 2018. In 2017, Viet Nam exported USD 45 million worth of tilapia to 68 markets. Government policies now focus on expanding commercial farming and exports, with a target of 400,000 tons of output by 2030 (SPIA, 2024).

After 20 generations of GIFT, CGIAR scientists have continued to improve tilapia strains, making them more resilient, disease-resistant, and rapid-growing. The breeding techniques developed through this project have also been successfully applied to other tilapia species in Egypt, Ghana, and Malawi, as well as to other fish, such as carp, creating widespread benefits for millions of people (Figure 21).

Which Decision-Makers Will Find This Useful?

National and local policymakers such as those in Ministries of Fisheries, Agriculture, Rural Development, Health and Finance. Non-governmental organizations (NGOs), and development agencies. Private sector enterprises seeking to benefit from setting up quality seed supply, fish feed supply, processed fish-based foods, and seaweed products, which sell at relatively higher prices than other food commodities.

Resources for Decision-Makers

Impact Evaluation

The Development of Genetically Improved Farmed Tilapia and their Dissemination in Selected Countries (Asian Development Bank)

Contact

Matthew Hamilton

Senior Scientist, CGIAR – WorldFish

m.hamilton@cgiar.org

Looking Ahead

Food and nutrition security challenges are expected to persist in sub-Saharan Africa, especially in regions where food systems are highly sensitive to climate change and many people depend on them for their livelihoods. This situation is worsened by supply chain disruptions in conflict-affected areas (ISDC, 2023). Emergency responses to conflicts and natural disasters, such as food and water aid to address acute hunger, can also divert resources from long-term efforts to build sustainable food systems that are resilient to these shocks. For example, it is important to provide consistent investment in staple crops (cereals), roots, tubers, and bananas that are expected to fare better in the changing climate, as well as foods from water and local foods that have the potential to contribute to healthy diets but often fall outside mainstream research and development efforts and budgets. Balancing long-term and short-term priorities requires planning based on sound science and cooperation among many different groups.

Investments in rural agricultural development also need to be balanced with meeting growing consumer demand in rapidly expanding cities for affordable, healthy diets. These investments can also offer a pathway to poverty alleviation by creating stronger links between rural food producers and creating job and enterprise opportunities along the value chain. Poverty is a key driver of malnutrition and food insecurity.

Urban food systems can support solutions through diversifying farming practices. These include:

- Diverse aquatic foods that emphasize the affordability of diets and reduce losses in perishable food chains.

- Fruit and vegetable production in hydroponic or aeroponic systems (when plants are grown without soil, using nutrient-rich water)

- Insect farming

- Vertical farming (where food is grown in stacked layers or tall structures, using controlled environments to maximize space and efficiency)

Support is also needed to improve food safety and quality in both formal and informal markets in low- and middle-income countries through better labeling, transparency, and traceability. This must be achieved without increasing costs for producers and consumers, as this can contribute to making healthy diets unaffordable.

Sustainable healthy diets promote all dimensions of an individual’s health and well-being. They are accessible, affordable, safe, and equitable, while being culturally acceptable and causing low environmental pressure and impact. Ensuring all of these characteristics is only possible if diets are considered within the wider context of the whole food system, from the farm to the consumer, and its links with numerous other sectors, from education to infrastructure. Nutrition efforts need to take a more comprehensive view of context to improve sustainable, healthy diets for the most vulnerable populations around the world.

Livestock and aquatic foods remain essential protein sources for both urban and rural communities. A promising area of work is to further understand how both can contribute to healthy diets, nutrition, livelihoods, and sustainability in food systems. Additionally, effective public and private sector partnerships are essential to expand and support public health efforts. These include reducing the consumption of sugar, oil, and salt, and cutting down on food waste.

Jump to Chapter