The gendered response to farmer-herder violent conflict in Nigeria

By Jeffrey Bloem, Amy Damon, David C. Francis, and Harrison Mitchell From 2010-2020, Nigeria experienced a sharp rise in violence propagated by the jihadist group Boko Haram in the northeast region and escalating inter-group conflict between farmers and Fulani pastoralists in the north-central region. Boko Haram’s violent attacks led to states of emergency in both 2011 and 2013; and while that

The gendered response to farmer-herder violent conflict in Nigeria

By Jeffrey Bloem, Amy Damon, David C. Francis, and Harrison Mitchell

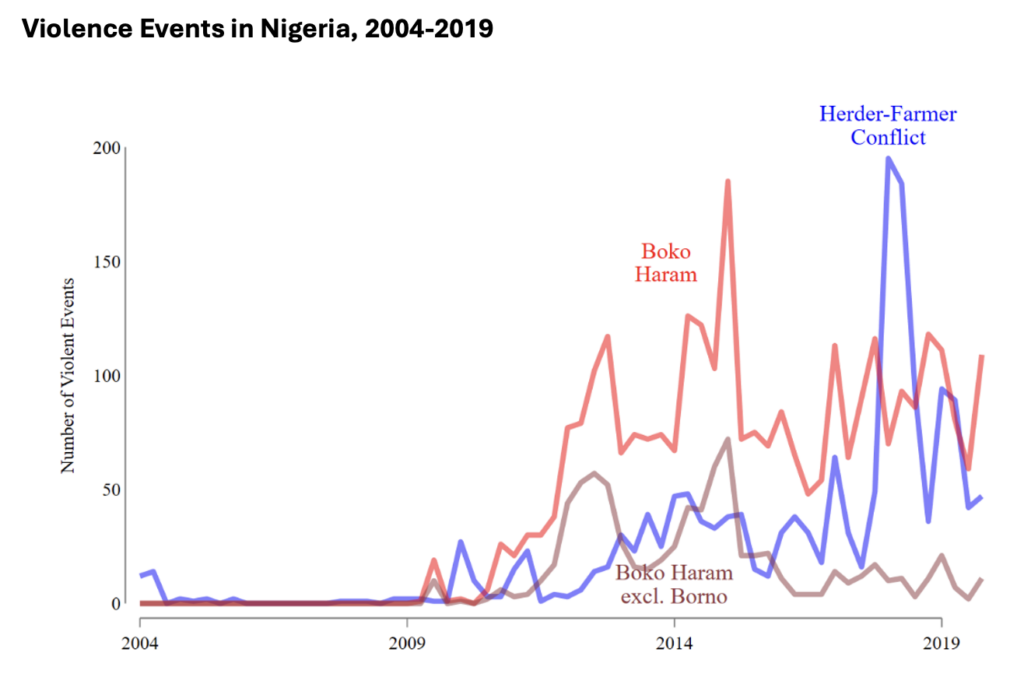

From 2010-2020, Nigeria experienced a sharp rise in violence propagated by the jihadist group Boko Haram in the northeast region and escalating inter-group conflict between farmers and Fulani pastoralists in the north-central region. Boko Haram’s violent attacks led to states of emergency in both 2011 and 2013; and while that group has dominated the news, conflicts between Fulani pastoralists and settled agricultural communities are often more deadly.

While the absolute number of incidents involving Boko Haram was higher over the 2004-2019 period (Figure 1), most of those attacks occurred in Borno state, the epicenter of that conflict. By contrast, the herder-farmer conflict grew in both intensity and geographic reach over this period, peaking in 2018 and becoming increasingly more prevalent than violence involving Boko Haram outside of Borno State.

Figure 1

Conflicts with nomadic herders present serious problems for smallholder agricultural households, disrupting farm work and financial market operations in affected areas. This raises the question: How do these households respond to and cope with exposure to violent conflict?

We address this question in a paper recently published in the Journal of Development Economics, finding that when households are exposed to multiple violent conflict incidents, there are changes in work patterns that often differ by gender, timing, and frequency of exposure.

Origins of recent herder-farmer conflict

The roots of Nigeria’s herder-farmer conflicts stem, in part, from competition over scarce land and water resources. Traditionally, an unwritten rule permits nomadic herders the open use of agricultural land during the dry season, the low period of agricultural activity. Farmers often welcomed the grazing as the wandering cattle naturally fertilized agricultural plots. At the end of the dry season, herders historically vacated agricultural land just in time for farmers to begin cultivating crops.

Yet the recent period of extended dry seasons and the Boko Haram conflict in the north have increasingly pushed herders south—and onto agricultural land—for longer periods of time. Consequently, the annual period preceding the planting season became a time of increased intensity in violent conflict between farmers and herders.

In response to tensions and outbreaks of violence between herders and farming communities, in 2016 and 2017 three Nigerian states—all traditional herding and farming areas—passed bans on open grazing. Ekiti state imposed the first in 2016 following the killing of two residents by herders, barring grazing activities in some areas and herders from carrying firearms (any herder found violating the arms ban could be declared a “terrorist” under the statute). In 2017, Benue and Taraba states passed strict open grazing prohibitions. Yet the restrictions did not have the intended result, leading instead to the 2018 spike in violence between herders and farming communities seen in Figure 1.

How do agricultural households respond?

Among the many sources of vulnerability smallholder agricultural households face, exposure to violent conflict is increasingly salient. This is especially true in countries with limited capacity to control such conflicts.

This vulnerability is amplified by at least two factors. First, temporal and geospatial patterns of conflict are often closely linked with agricultural seasons, droughts, and contested access to natural resources such as land and water, thus placing agricultural households in close proximity. Second, financial markets in low- and middle-income countries—including banks and insurance markets—often function poorly in rural areas and in agricultural contexts, and conflicts hamper their operations further.

To study how smallholders respond to these problems, we combine detailed panel data of households and individuals from Nigeria’s General Household Survey (GHS) with data on violent events from the Armed Conflict Location and Event Data (ACLED) project. The GHS data contains four survey rounds, each including two seasonal visits—post-planting and post-harvest—allowing us to observe individuals up to eight separate times between 2010 and 2019.

With these data, we leverage variation across time and space as our primary indicator of exposure to farmer-herder violence, defined as the presence of farmer-herder violent conflict incidents within a 10-kilometer radius around households and taking place within one month before the survey response. To assess previous exposure, we examine violent conflict incidents occurring in the same 10 km area and from one to six months before the survey.

The granularity of these data allows us to include both time and individual fixed effects, to estimate changes in economic activities associated with farmer-herder violence while ruling out confounding variation between individuals over time. We also restrict comparisons in two ways: By the planting or harvest seasons and by gender, allowing us to estimate specific seasonal and gendered labor responses.

Our findings show that individuals in agricultural households make labor allocation decisions differently based on the timing of conflict exposure relative to three factors: The agricultural season, the individual’s gender, and whether exposure represents a singular event or a repeated event. The latter finding suggests that these effects seem to operate through a mechanism that we call the “shadow of violence,” whereby previous exposure to a violent event casts a shadow over and alters responses to a more recent event.

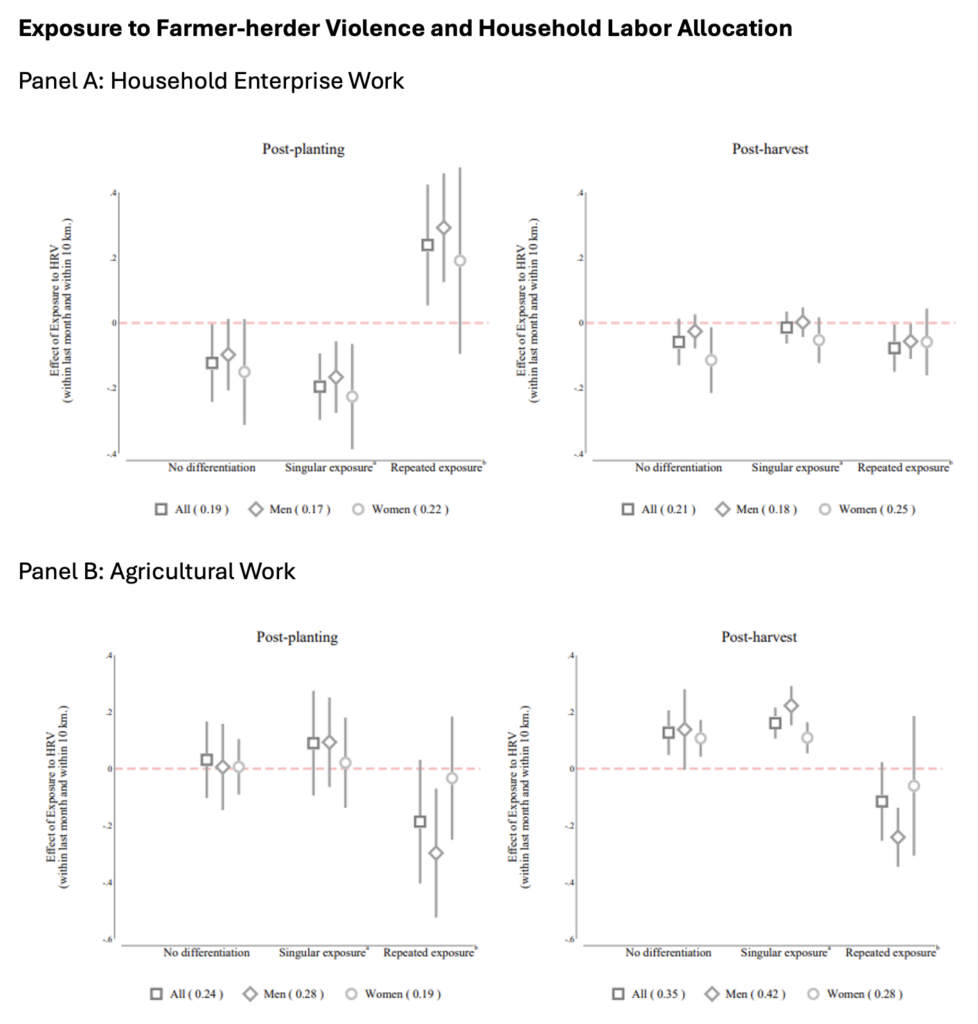

Our main results, shown in Figure 2, reveal that in the post-planting season, individuals within agricultural households exposed to a single farmer-herder violent conflict event reduce household enterprise work and do not change agricultural work.

When individuals are exposed to repeated conflict events, however, we observe different household labor responses by gender.

During the post-planting season, women in such households work more total hours; while among men, exposure leads to a shift toward household enterprise work that seems to act as a substitute activity for agricultural work.

During the post-harvest season, men reduce agricultural work, while we find no such effects among women.

One potential source of conflict resilience for smallholders is non-farm household enterprises that can help make up for lost agricultural income. Yet our analysis shows that exposure to farmer-herder violence does not lead to reported increases in sales from such enterprises.

Thus, while we do find that affected households might use such enterprises as a response mechanism to the increased risk associated with agricultural production, this behavior does not seem to effectively guard against adverse economic consequences.

Figure 2

Notes: The vertical axis plots the magnitude of the marginal effect, and associated 95% confidence intervals, of exposure to a herder-related violent event (HRV)

on household enterprise work (panel A) and agricultural work (panel B). Sample means of the outcome are in parentheses in the legend. The figure shows results

from two specifications: The first does not differentiate by previous exposure. The second differentiates by previous exposure. a ‘singular exposure’ denotes HRV

exposure not under the shadow of violence; b plots the effect of an additional HRV event while also experiencing other recent violence (that is, repeated violence

under the shadow of violence). Estimates by Bloem et al. (2025). Shared with permission by the authors.

Indirect costs of violence

Farmer-herder violence, therefore, can have wide-reaching indirect costs beyond the loss of human life and the destruction of property. To address these problems, the ultimate policy goal is to reduce the prevalence of farmer-herder conflict. Yet this is a difficult challenge, as demonstrated by the sharp rise in farmer-herder violence after the implementation of policies that effectively excluded herders and favored farming communities. Evidence shows, however, that including herding communities in the policy process can moderate farmer-herder violence.

In the meantime, future policy and research efforts could focus on understanding how best to supplement informal coping mechanisms by providing formal economic support for households exposed to violence and conflict. For instance, understanding the gendered nature of household responses to farmer-herder violence motivates interventions that account for the unequal burden of informal coping mechanisms within smallholder agricultural households.

Jeffrey R. Bloem is a Research Fellow with IFPRI’s Markets, Trade, and Institutions Unit; Amy Damon is a Professor of Economics at Macalester College; David C. Francis is a Senior Economist at the World Bank; Harrison Mitchell is a Ph.D. student at the University of California San Diego. Opinions are the authors’.

This work was supported by the CGIAR Science Program on Food Frontiers and Security.

Header Photo caption: Fulani herders guide their cattle down a road in Nigeria. Photo Credit: Carsten ten Brink via Flickr

Referenced paper:

Bloem, Jeffrey R.; Damon, Amy; Francis, David C.; and Mitchell, Harrison. 2025. Herder-related violence, labor allocation, and the gendered response of agricultural households. Journal of Development Economics 176 (September 2025): 103512. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2025.103512