What 50 Years of Food Systems Research Reveal About Transformation

Over the past 50 years, CGIAR research has shaped how food systems are understood and transformed. This blog distils key insights from that body of work and what they mean for addressing today’s food, climate, and development challenges.

Why food systems transformation matters now

The food system refers to a combination of all subsystems that includes actions ranging from production to the consumption of food on a day-to-day basis1. Food systems shape far more than what ends up on our plates. They determine how land is used, how labor is valued, how ecosystems are managed, and who bears the risks of climate change, market shocks, and political instability. In recent decades, these systems have come under unprecedented strain. Climate disruption, biodiversity loss, supply-chain volatility, dietary transitions, and widening inequality have exposed vulnerabilities across production, distribution, and consumption. As a result, global conversation has expanded to not only include improving yields but to also question whether the existing food system itself is fit for a sustainable future. There is a growing call for food systems transformation with an idea that incremental reform is no longer sufficient and that deeper structural change is required.

Studies have shown that food systems transformation (FST) globally can result in substantial economic returns, amounting to approximately $10 trillion annually 2. Systematic attention to FST has gone beyond agricultural policy reforms3,4. Specific components of the FST, for instance, climate resilience crops, food loss and waste5, technological innovation6, adequate biosafety levels7,8, and healthy consumption patterns 3, to name a few, have received substantial inquiry. At a holistic level, topical issues such as systems thinking 9, funding, multi-sectoral collaboration10, economic incentives, market externalities, and monitoring & evaluation have received deeper attention11. At both specific and holistic levels, there is a rightful urgency to expedite transformation in food systems globally. Consequently, there has been a significant increase in publications on FST over the years, spanning multiple academic disciplines and geographical settings. Thus, over the past two decades, research using FST has surged, spanning agriculture, nutrition, economics, technology, public health, and social justice. Yet despite its popularity, “transformation” remains an unsettled concept. Scholars often work in parallel rather than in conversation, advancing different visions of change shaped by disciplinary priorities, institutional incentives, and regional contexts. This fragmentation matters. When knowledge production is siloed, policies become harder to coordinate, investments risk reinforcing inequities, and ambitious rhetoric outpaces practical integration. Understanding how this field has evolved—and who is shaping is essential for turning transformation from aspiration into action.

Researchers have done systematic reviews on FST12,13. However, systematic reviews despite its own inherent merits, fall short in providing an objective inventory of the main scientific trends, patterns, and gaps across time and geographical settings. There is no comprehensive analysis on FST, which has analyzed publications, citations, authorships, and keywords to examine the intellectual structure, trends of publications, and future directions.

How we mapped the field

We conducted a large-scale bibliometric analysis of FST spanning more than five decades of research to scientifically map global research network for an overview of existing knowledge, unpack high-impact areas, and inform decision-making. Rather than reviewing individual studies, bibliometrics maps the structure of an entire field, revealing dominant themes, influential institutions, geographic concentrations, and patterns of collaboration across thousands of publications. We analyzed manuscripts (written in English) published between 1972 and 2024 (both inclusive), which were indexed in three major scientific databases—Scopus, Web of Science, and PubMed. Since FST is a field that has a critical mass of both academic researchers and field practitioners, we examined diverse entries including peer-reviewed articles, reports, commentaries, conference proceedings, book chapters, and editorials, to list a few. To capture the breadth of how transformation has been discussed over time, we used a deliberately expansive set of search terms, including “food systems,” “food systems transformation,” “food systems transition,” and “food value chain transformation.” These terms were applied to article titles, abstracts, and keywords, producing a final dataset of 24847 entries after removing duplicates. Using biblioshiny package in R version 4.5.1 and VOSviewer, we examined the data to explore the intellectual landscape of food systems transformation. To the best of our knowledge, there is no other bibliometric review in the current literature that explores over 50 years of research on FST, and with such in-depth analyses.

What Fifty years of FST research reveal: Key findings

Food systems transformation research has grown explosively—but only recently.

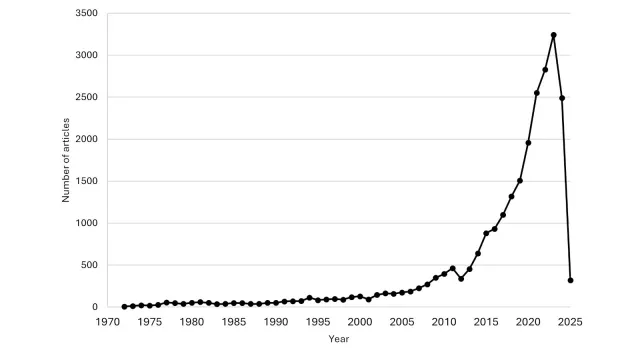

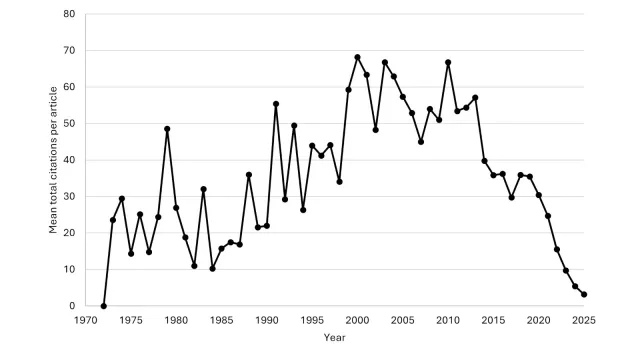

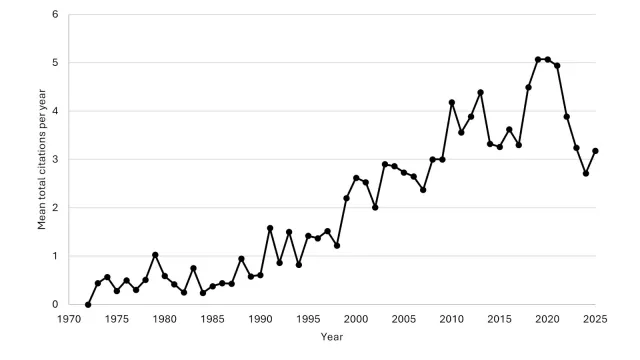

Although early systems-oriented food research dates back to the 1970s, the field remained relatively contained for decades (see Figure 1). Impressive growth began in the early 2000s and accelerated sharply after 2010, with publication output peaking in 2023 at more than 3,200 articles in a single year. This surge mirrors the convergence of global crises—climate change, food insecurity, biodiversity loss, and rising diet-related disease—that have pushed food systems to the center of sustainability and development debates. Citation patterns reinforce this trajectory (see Figure 2 and Figure 3). The work published in the late 1990s and early 2010s has accrued the highest total citations, while more recent research shows strong citation momentum but limited accumulation due to time lag. Together, these trends point to a field that has moved rapidly from the margins to the mainstream, expanding faster than it has stabilized conceptually.

The field is framed around “systems,” but anchored in a narrow sustainability–security core.

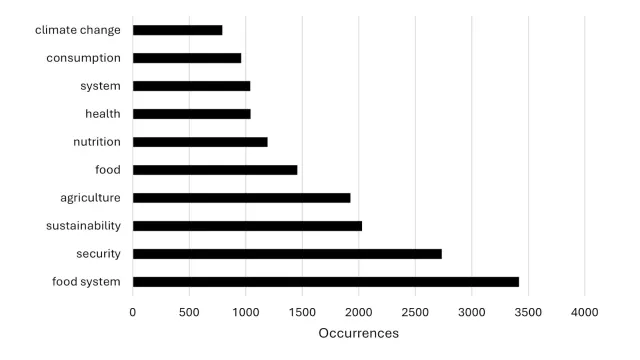

As shown in figure 4, across more than 24,000 publications, the most frequently used keywords center on food systems, sustainability, security, agriculture, nutrition, and health. This reflects broad agreement that food-related challenges are interconnected and must be addressed holistically. Yet co-occurrence analysis reveals a dense and hierarchical conceptual core dominated by environmental sustainability, agricultural production, and food security. Climate change, resilience, and biodiversity are tightly integrated into this core, shaping how transformation is most often imagined. While systems language is widespread, it is primarily mobilized through environmental and production-oriented frameworks rather than through governance, political economy, or social power lenses.

Conceptual integration remains uneven and hierarchical.

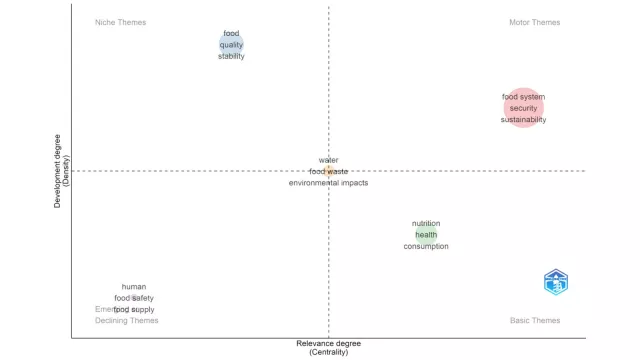

Thematic mapping (Figure 5) shows that sustainability and food system security function as the field’s “motor themes”—highly developed and deeply embedded in the literature. Nutrition, health, and consumption are also central but comparatively underdeveloped, suggesting frequent reference without cohesive theoretical consolidation. In contrast, technically focused areas such as food quality, stability, and food science are internally well-developed but weakly connected to broader transformation debates, that are within the realm of social sciences. Critical knowledge related to food safety, processing, and preservation remains siloed from system-level discussions, reinforcing a field organized around a dominant sustainability–security core with other dimensions occupying more peripheral roles.

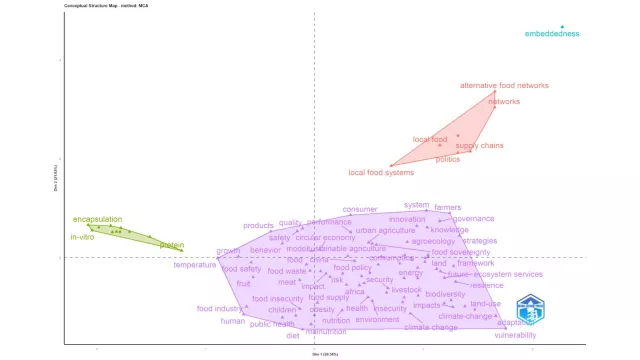

Distinct research strands operate in parallel rather than in dialogue.

Figure 6 highlights clear separations within the literature. System-level, climate-oriented research forms the dominant conceptual cluster, where governance, nutrition, agriculture, and adaptation are frequently addressed together. Localized food systems research—focused on supply chains, networks, and alternative food models—and technical food science research cluster separately, with limited conceptual overlap. Some theoretically important concepts remain strikingly isolated. For example, embeddedness, which captures how economic activity is shaped by social and political context, appears disconnected from dominant research clusters despite its relevance to real-world food systems. FST as a field will benefit with integration of technical and social sciences. However, it appears that segmentation in fields continue beneath the surface.

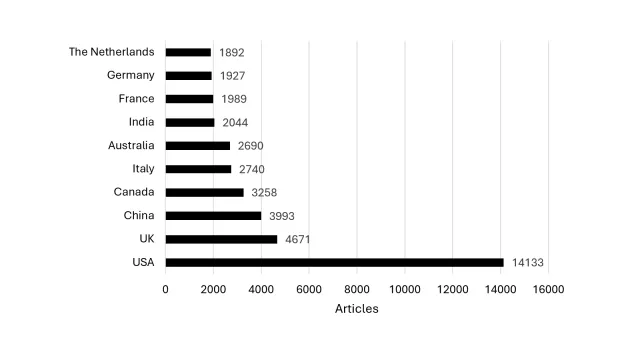

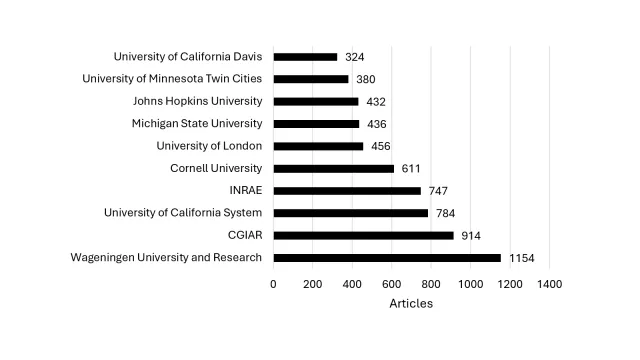

Knowledge production is geographically and institutionally concentrated.

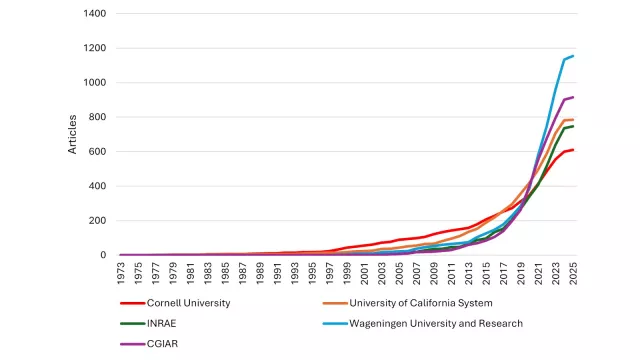

Food systems transformation scholarship is dominated by a small number of countries and institutions. As shown in Figure 7, the United States and Europe account for the majority of publications and citations, with no countries from Latin America or Africa appearing among the most prolific producers. Figure 8 and 9 shows that at the institutional level, Wageningen University & Research and CGIAR emerge as the most central and productive contributors, functioning as global collaboration hubs. Other leading institutions—including the University of California system, INRAE, and Cornell University—are similarly well-resourced organizations in the Global North. This concentration suggests that dominant visions of transformation are shaped primarily by actors with access to substantial research infrastructure, raising questions about whose experiences, priorities, and knowledge systems remain underrepresented.

What this means for the future of food systems transformation

Our findings suggest that food systems transformation research is shaped less by global need than by research capacity. A small group of countries—particularly the United States, Western Europe, and China—dominates publication output, reflecting differences in funding, institutional scale, and research infrastructure. Countries (such as the US) with large domestic research systems and infrastructure tend to rely heavily on single-country publications. However, there are European nations, that exhibit higher levels of international collaboration. Yet the absence of Latin American and African countries among the most prolific contributors raises a critical concern: regions facing the greatest food system vulnerabilities remain marginal in defining what “transformation” means at a global level.

At the same time, collaboration does not necessarily translate into conceptual integration. Despite extensive international networks, food systems transformation scholarship remains fragmented across parallel research communities, disciplines, and thematic priorities. Highly influential work often circulates within distinct clusters, limiting cross-fertilization among technical, environmental, social, and governance-oriented approaches. If food systems transformation is to fulfill its promise, the field must move beyond expanding output and connectivity toward deeper intellectual integration—bridging disciplines, regions, and ways of knowing to align transformative ambition with inclusive and context-responsive knowledge.

References

1 . Stefanovic, L., Freytag-Leyer, B. & Kahl, J. Food system outcomes: an overview and the contribution to food systems transformation. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems 4, 546167 (2020).

2 . 2024 Global Food Policy Report: Food Systems for Healthy Diets and Nutrition. (International Food Policy Research Institute, Washington, DC, 2024).

3 . Ruben, R., Cavatassi, R., Lipper, L., Smaling, E. & Winters, P. Towards food systems transformation—five paradigm shifts for healthy, inclusive and sustainable food systems. Food Security13, 1423-1430 (2021).

4 . Fan, S. & Swinnen, J. Reshaping food systems: The imperative of inclusion. Global Food Policy Report, 6-13 (2020).

5 . Alexander, P. et al. Losses, inefficiencies and waste in the global food system. Agricultural systems 153, 190-200 (2017).

6 . Von Braun, J., Afsana, K., Fresco, L. O. & Hassan, M. H. A. Science and innovations for food systems transformation. (2023).

7 . Wielinga, P. R. & Schlundt, J. One health and food safety. Confronting Emerging Zoonoses: The One Health Paradigm, 213-232 (2014).

8 . Wu, D., Elliott, C. & Wu, Y. Food safety strategies: the one health approach to global challenges and China’s actions. China CDC weekly 3, 507 (2021).

9 . Zhang, W. et al. Systems thinking: an approach for understanding'eco-agri-food systems'. (2018).

10 . Herens, M. C., Pittore, K. H. & Oosterveer, P. J. Transforming food systems: Multi-stakeholder platforms driven by consumer concerns and public demands. Global Food Security 32, 100592 (2022).

11 . Diaz-Bonilla, E. Transformation of food systems: How can it be financed? Frontiers of Agricultural Science & Engineering 10 (2023).

12 . Juri, S., Terry, N. & Pereira, L. M. Demystifying food systems transformation: a review of the state of the field. Ecology and Society 29 (2024).

13 . Van Bers, C. et al. Advancing the research agenda on food systems governance and transformation. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability 39, 94-102 (2019).

Contributors:

Nuasheen Chowdhury*, Erin Marmen*, Wei Zhang#, and Praveen Kumar*

*Boston College, Chestnut Hill, USA

#International Food Policy Research Institute, Washington, DC, USA